A few years ago at our CVPR 2023 Transformers for Vision workshop, Lucas Beyer said something offhand that struck me by surprise which I’ve been trying to piece together ever since. The interaction went something like this:

Question from the audience: “Why aren’t we scaling vision models as large as we do LLMs?” “You know, actually, the largest vision models are on par with the largest language models if you look at [X].” - Lucas

I can never quite remember what X was, if it was FLOPs, parameters, or token budget. Obviously now it’s not parameters, as the largest recorded ViTs still tap out in the 22B regime (with the most consistent scaling amounts being 1B-7B as in DINOv3 [14], etc.).

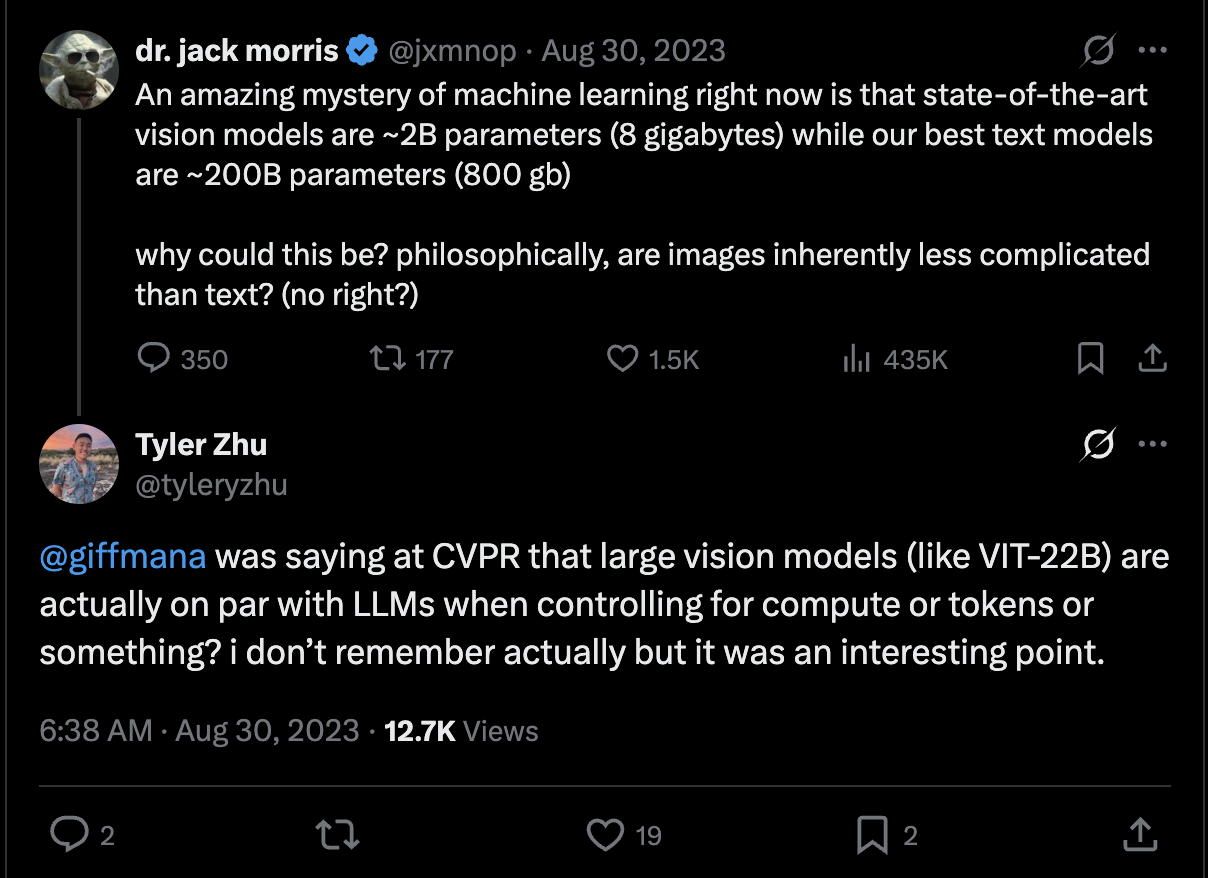

X conversation with Jack Morris: https://x.com/tyleryzhu/status/1696653496626380970?s=20

This mystery still somewhat holds true, and I think about this often enough where I’ve decided to try and trace down the original point (with Gemini as my somewhat-reliable research assistant).

X marks the treasure, and potentially AGI

Among the possibilities, parameters is clearly not it. If anything, vision models are surprisingly parameter efficient for their capabilities. I would argue that vision models haven’t found enough signal to benefit from scaling, as despite the best efforts shown in works like ViT-22B [4] and more recently 4DS [13], works like DINOv3 [14] have found large vision models to be terribly unstable to train. In fact, anecdotally, I found these larger models to have worse performance than their smaller sized 1B variants (e.g. in my latest paper on video-text alignment), but YMMV.

Another good candidate is FLOPs, i.e. compute invested during training. To do that, we need to compute tokens, as FLOPs = tokens x FLOPs per token ~ tokens x params.

For this comparison, I will sample a few of the models which came out before this interaction happened (June 2023). This means

Large Language Model FLOPs

Llama-2 [2] has three sizes identical to those of its predecessor: 7B, 13B, and 70B. Each model is trained on 2.0T tokens (de-duplicated) with a context length of 4k.

We’ll estimate the FLOPs as a function of the sequence length, layers, hidden dimension, and heads $N, L, D, H$. Per attention block, we have:

- Attention QKV: Each is a matrix multiplication $[N\times D] \times [D \times D] \to 2ND^2$. One for each gives $6ND^2$.

- Attention scores: This is $QK^T$, which is $[N\times D]\times[D\times N] \to 2N^2 D$. There is normalization and softmax but those are dominated by this term, and the heads don’t affect FLOPs.

- Values: This is $[N \times N] \times [N \times D] \to 2N^2 D$.

- Output: This is $[N\times D] \times [D \times D] \to 2N D^2$. In total, this is $8ND^2 + 4N^2 D$.

For the feed forward block, we have a $[D \to 4D \to D]$ connection, which results in $16ND^2$ in total.

So for one transformer block, we have $24ND^2 + 4N^2 D$, and $3BL$ times that for the total count ($BN$ is the same as the total token count, and 1 for forward + 2 for backward).

Our parameter count is $4D^2$ for $Q,K,V,O$ and $8D^2$ in the FFN, so $12D^2$ in all. When $D » N$, we obtain a common approximation for the amount of FLOPs in a forward + backward pass: $$ \text{FLOPs} \approx 72ND^2 = 6\times \text{params} \times \text{tokens}.$$ However, just to stay even with how vision researchers (like myself) calculate FLOPs, we’ll keep track of just the forward FLOPs (which is just a third of the total anyways). So our final formula is $$ \text{fwd FLOPs} \approx L(24ND^2 + 4N^2D) \approx 2\times \text{params} \times \text{tokens}.$$ Below are the stats of the model from largely the Llama-1 [1] paper. As you can see, in this case, $D$ is approximately the same as $N$, so this approximation doesn’t seem to hold.

One small detail: Llama-2 70B actually uses Grouped-Query Attention, which reduces the KV-cache by making multiple queries share the same KV vectors, so its FLOP count is slightly off. It uses 64 query heads ($H_q$), but 8 kv heads ($H_{kv}$), which means the $KV$ projections are $2ND^2 \to ND^2 / 4$. The total QKV FLOPs then is $2.5ND^2$, or $4.5ND^2 + 4N^2D$.

| Model | $N$ | $L$ | $D$ | $H$ | tokens | FLOPs/tkn | total fwd FLOPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Llama-2 7B | 4096 | 32 | 4096 | 32 | 2.0 T | 14 G | 28T GFLOPs |

| Llama-2 13B | 4096 | 40 | 5120 | 40 | 2.0 T | 26.56 G | 53T GFLOPs |

| Llama-2 70B | 4096 | 80 | 8192 | 64 | 2.0 T | 130 G | 260T GFLOPs |

Vision Transformer FLOPs

Now let’s look at the Vision Transformers. I couldn’t find enough details about the exact compute budget of SigLIP, but the “Getting your ViT in shape” [6] paper is a great reference for this purpose (of course it is!), so I’ll substitute in the SoViT-400m/14 model for it. There’s lots of discussion about everything in terms of compute budgets and parameter counts, especially how FLOPs correlates well with the amount of TPU core-hours spent (so it’s a decent proxy!).

I’m looking at purely the largest size for each one. Here’s the spec for each architecture, on a constant patch size of 14x14 (varying input image size as indicated by patches). These are actual traced numbers, so the comparison with LLMs won’t be entirely fair, but at least it’s close!

| Model | params | patches | width | depth | dim | FLOPs/tkn | pretrain | tokens | total fwd FLOPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SoViT-400m/14 | 428M | 256 | 1152 | 27 | 4304 | 0.86 G | 40B (~13e) | 10.2 T | 9T GFLOPs |

| SoViT-400m/14 | 428M | 1369 | 1152 | 27 | 4304 | 1.00 G | 6.5B (~2e) | 8.9 T | 9T GFLOPs |

| DINOv2-g^^ | 1.01B | 256 | 1408 | 40 | 6144 | 2.08 G | 7.1B (~50e)^ | 1.8 T | 3.8T GFLOPs |

| ViT-22B | 22B | 256 | 6144 | 48 | 24576 | 40.78 G* | 11.5B (~3e) | 2.9 T | 120T GFLOPs^^^ |

^ estimated from the only training recipe of 500 epochs of ImageNet-22k (14M images)

^^ using a true ViT-g shape, from which the DINOv2 model is slightly modified from. also not counting the teacher + student

^^^ estimated using the formula

Interestingly, our estimate above from the LLMs isn’t entirely accurate for ViTs. The MLP expansion factor for larger ViTs is usually not 4.0, but rather 3.7 ish. If we account for the actual expansion factor $\alpha$, then the corrected estimate for FLOPs / parameter becomes $$(8 + 4\alpha) / (4+2\alpha) = 2 $$ so it turns out to not be much of an issue! The rest of the error in our simple approximation is resolved with the full form above.

Musings

The first thing that I was most surprised by in my research was how total FLOPs was the appropriate baseline to compare models across. It’s somewhat obvious in hindsight, but coming from epoch-land in vision made it less clear at first.

Unsurprisingly, it seems that vision researchers were far off from hitting the same total FLOP count as language researchers until we scaled up both our model and dataset size. ViT-22B is the closest we have, having reached 120T GFLOPs which puts it squarely in Llama territory, and makes me believe that our X is indeed total FLOP count.

However, the gains from this weren’t as ground breaking as what we’d expect from an LLM of similar scale. There’s a few things I noted.

First, ViTs will find it hard pressed to go beyond short sequence lengths to great success. This can artificially “inflate” the pretraining token amount, but such gains are not for free. There’s some benefit to having larger images, but eventually there is diminishing return (see Figure 7 in [6]). Fundamentally, the signals gained from higher resolutions are largely overlapping with those present on smaller images, and likewise with multi-epoch training (which vision is stuck in). We need more sources of signal, and more tokens of it, which likely could come from video, or joint text-image data as is already done. In other words, not all FLOPs are created equal.

This points to the information disparity between language and vision tokens which many of alluded to. I first heard of this from (someone else from) Kaiming in a talk, remarking how BERT’s optimal masking ratio is 15% [7] compared to MAE’s 75% [8] and ST-MAE’s 90% [9] suggests that vision tokens are largely redundant and not as information dense. Since then, I’ve seen this idea in Transfusion [10]/Chameleon [11], noting how it was difficult to train such mixed modality transformers due to the loss imbalance from both modalities. This was a focal point of their followup work MoE-Sparsity [12].

Second, these aren’t entirely comparable because all of the models are using wildly different training methods. LLMs are built on next token prediction, i.e. conditional soft classification, whereas ViTs use SSL and one-hot classification (supervised learning). It’s still unclear how these objectives affect the scaling, or if there’s a different factor which could predict all of them.

Finally, given that the performance of these models does not differ heavily with FLOPs/token, either our tokens need to be more informative for us to invest so much compute into them, or we need to be smarter in how we invest our compute: adaptive compute maybe, but I think we need to first figure out how we can use more, effectively, before optimizing it.

Citations

[1] Touvron et al., “LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models”, arXiv 2023.

[2] Touvron et al., “Llama 2: Open Foundation and Fine-Tuned Chat Models”, arXiv 2023.

[3] Zhai et al., “Sigmoid Loss for Language Image Pre-Training”, arXiv 2023.

[4] Dehghani et al., “Scaling Vision Transformers to 22 Billion Parameters”, arXiv 2023.

[5] Oquab et al., “DINOv2: Learning Robust Visual Features without Supervision”, arXiv 2023.

[6] Alabdulmohsin et al., “Getting ViT in Shape: Scaling Laws for Compute-Optimal Model Design”, NeurIPS 2023.

[7] Devlin et al., “BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding”, arXiv 2019.

[8] He et al., “Masked Autoencoders Are Scalable Vision Learners”, arXiv 2022.

[9] Feichtenhofer et al., “Masked Autoencoders As Spatiotemporal Learners”, arXiv 2022.

[10] Zhou et al., “Transfusion: Predict the Next Token and Diffuse Images with One Multi-Modal Model”, arXiv 2024.

[11] Chameleon Team, “Chameleon: Mixed-Modal Early-Fusion Foundation Models”, arXiv 2024.

[12] Kilian et al., “Improving MoE Compute Efficiency by Composing Weight and Data Sparsity”, arXiv 2026.

[13] Carreira et al., “Scaling 4D Representations”, arXiv 2024.

[14] Simeoni et al., “DINOv3”, arXiv 2025.