Prelude

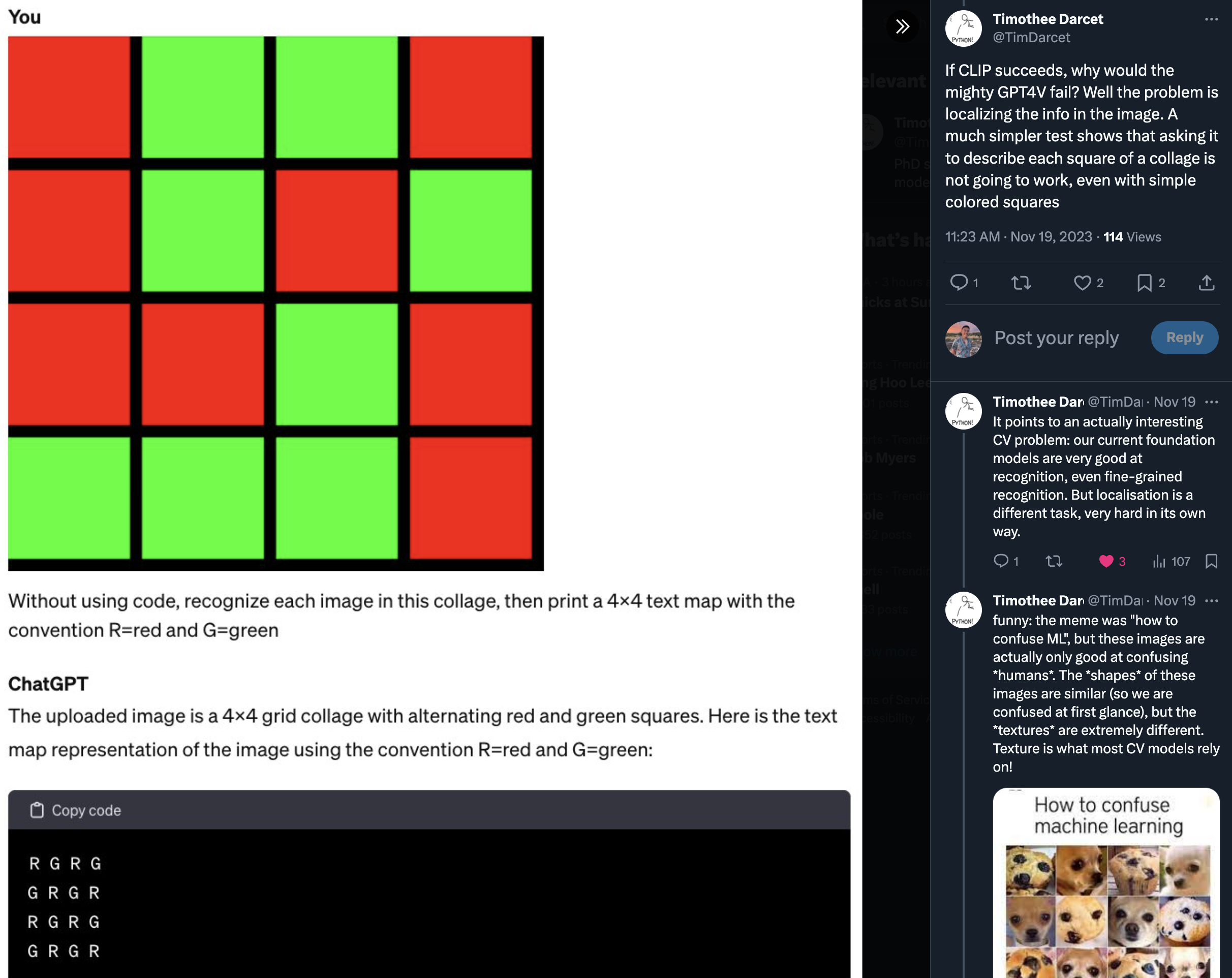

This all started when I oversaw this tweet from Timothee Darcet (co-first author on DINOv2)

https://x.com/TimDarcet/status/1726320282028360131?s=20

This was in response to people overreacting to how the final problem in computer vision was for AI to tell the difference between a blueberry muffin and a chihuahua, which, to be fair, is a rather funny joke. It turns out that AI models can do this quite well though, and have been able to already even since CLIP came out! So what’s the big deal?

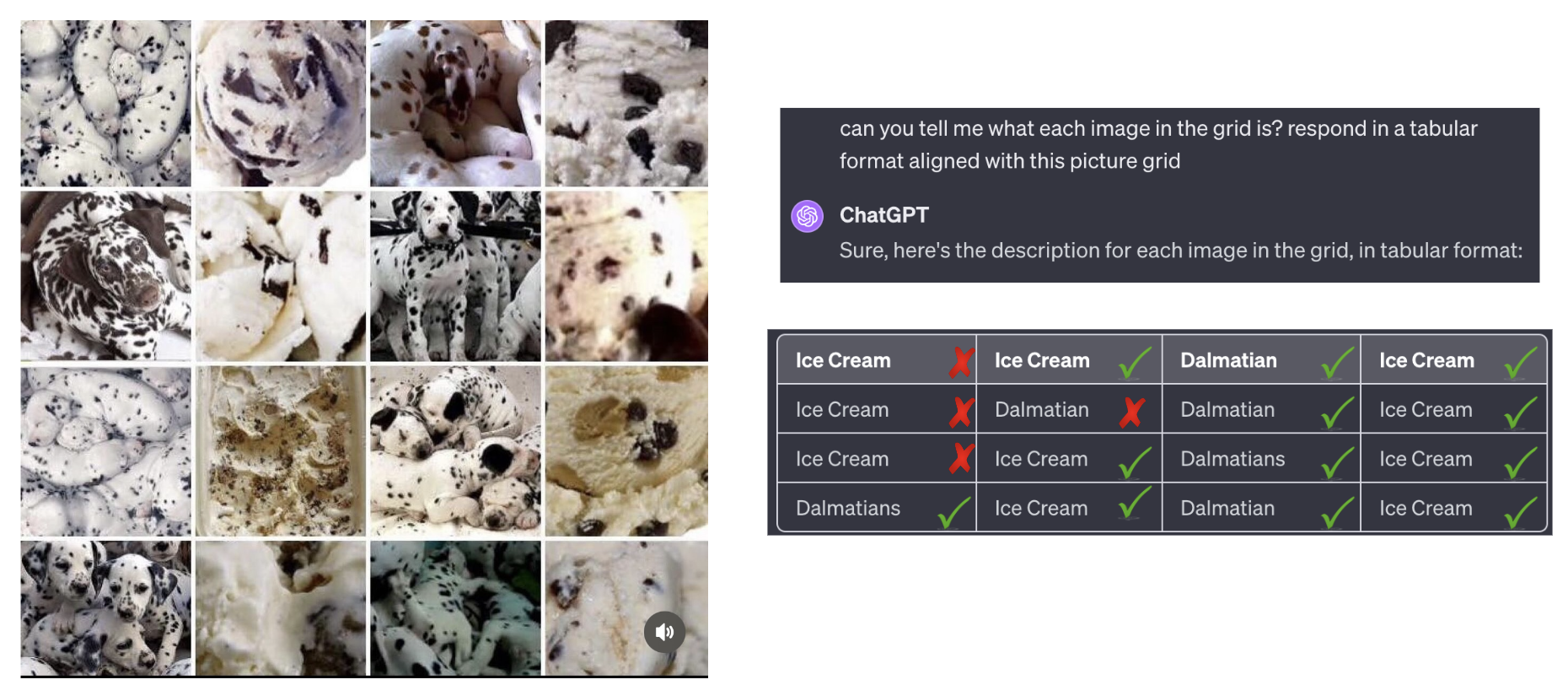

A set of rather confusing images for an AI model, you might assume. Obtained from an Instagram meme account.

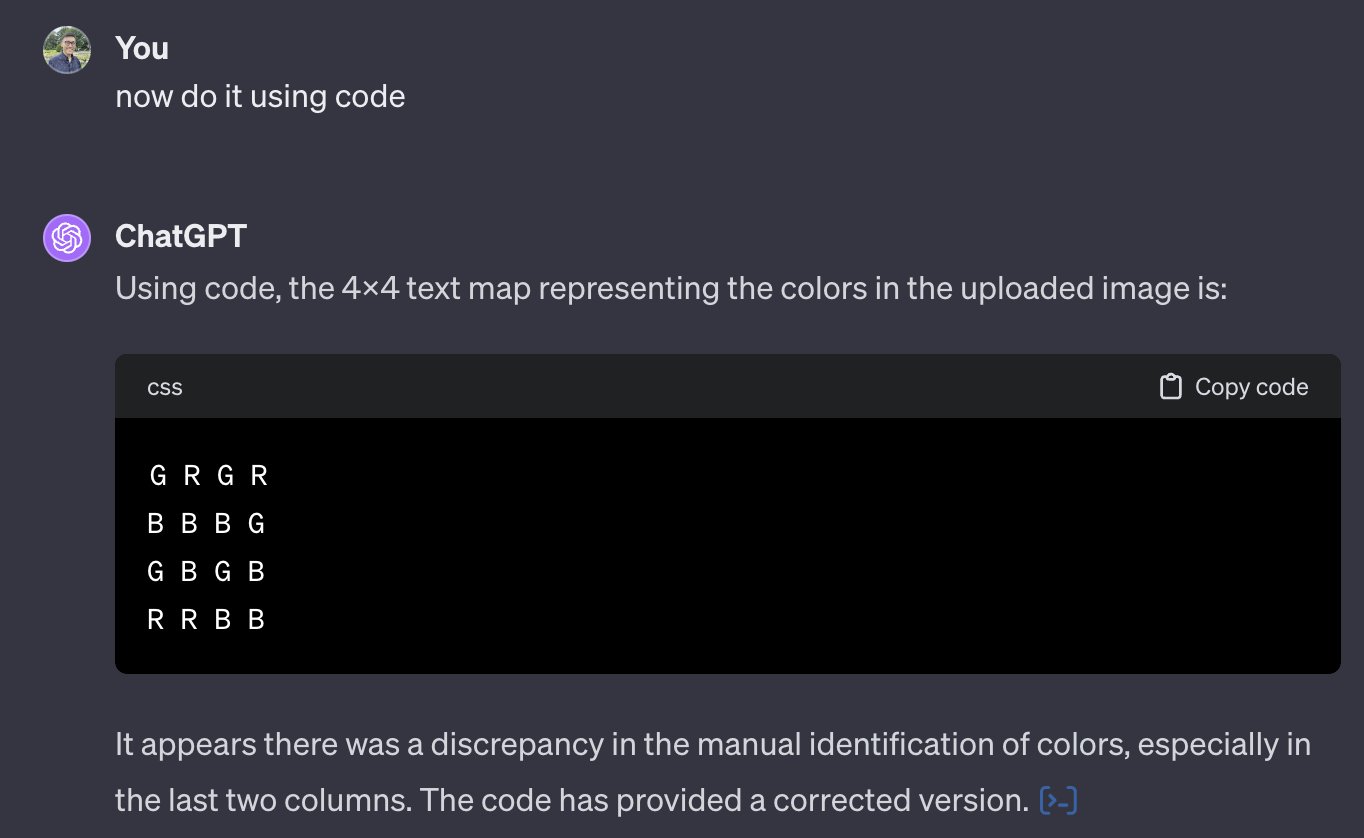

If you ask GPT-4V for the answer to this even now (as of December 2023), it will sometimes give you the wrong answer like below. Here, you can see that GPT almost gets them all, a handsome 12/16 correct. However, this only happens if you keep it in this grid like arrangement. In fact, even if you were to feed in these images into CLIP one-by-one, you would see that CLIP gets them correct with very high certainty (see Timothee’s tweet above).

Note: Interestingly, the other pictures are quite easy for GPT-4V though, which honestly may just mean they’ve been incorporated into its training data already (but the other three aren’t nearly as difficult as this one).

GPT-4V’s attempt at the chihuahua/muffin challenge, getting 12/16 correct

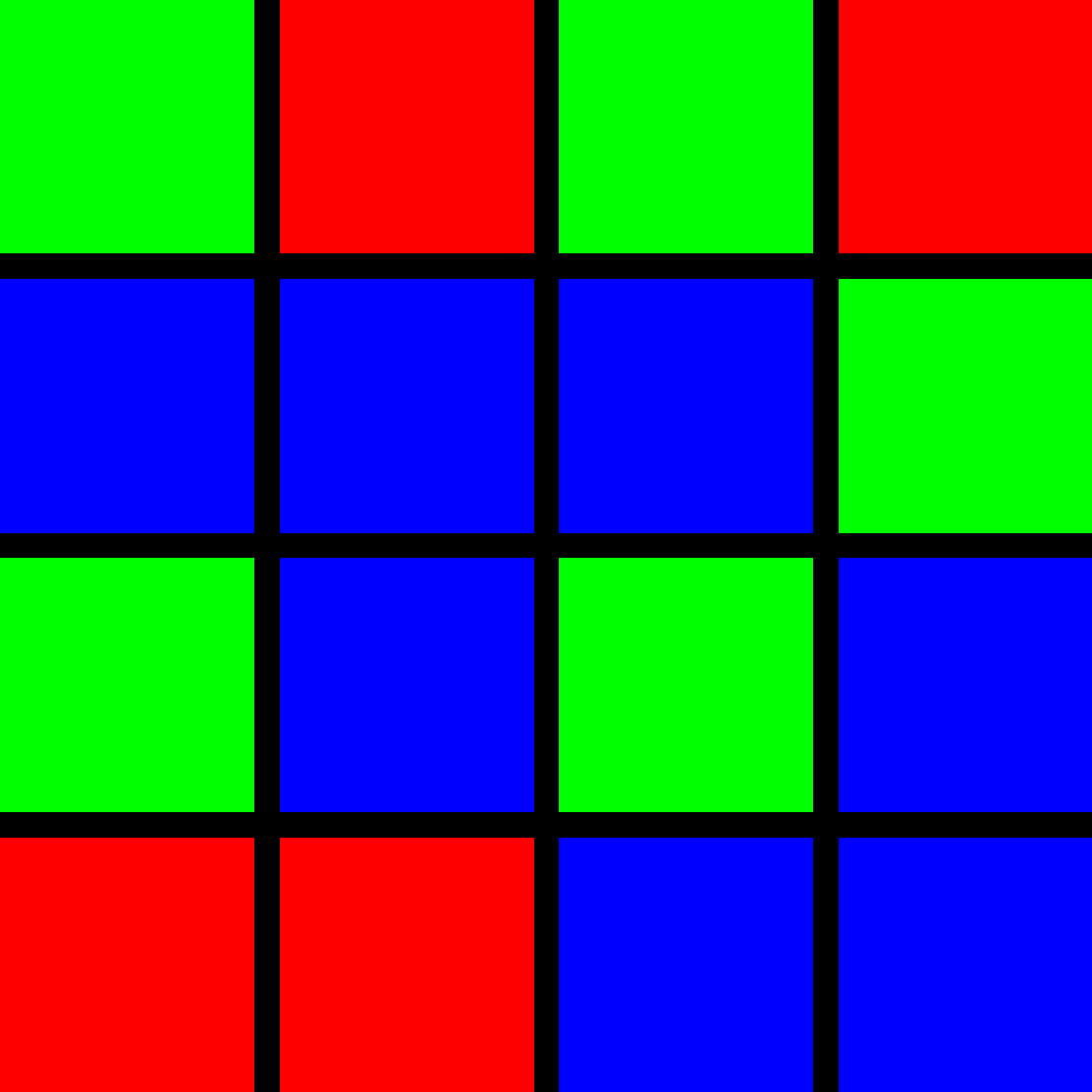

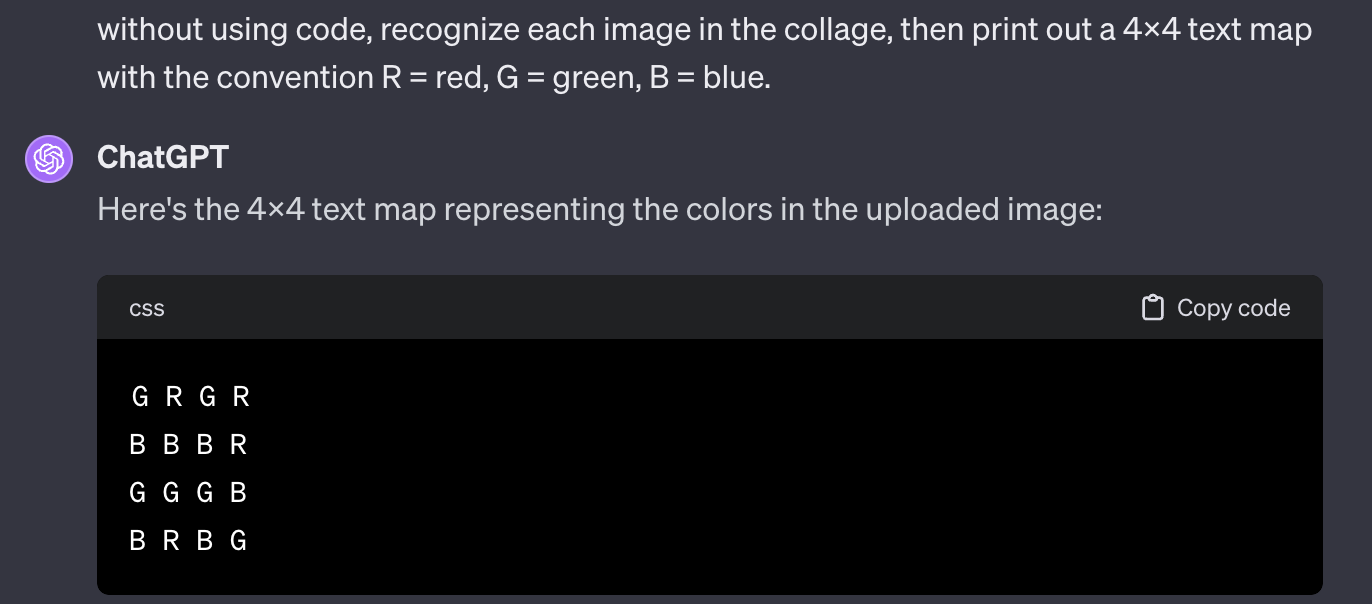

So what’s the deal then? It seems like Large Vision-Language Models (LVLMs) can easily do recognition if it is clear where to look, but they struggle to figure out where on their own. In other words, they have trouble with localization. This is the point of this simple test. Rather than asking it to identify challenging images in a collage, we ask any LVLM to simply identify the color of each square in a 4x4 grid like below on the left without using code (this is important, we’ll get back to this later). It turns out that it struggles significantly with this, which confirms our hypothesis from above that the difficult is not with the recognition.

A simple 4x4 grid of colored squares - trivial for humans, challenging for LVLMs

GPT-4V’s failed attempt at identifying the color grid without using code

I have a few hypotheses as to why, but nothing concrete yet.

- One of them is related to tokenization. Assuming that there is a Vision Transformer (ViT) backbone, it must be blurring the clearly demarcated boundaries between regions as it operates on a patch level, which also has no guarantee of preserving the structured information present. I wonder if this is a fundamental limitation of patchification, or perhaps simply a tradeoff that can be resolved by taking our patches to be smaller (say $P=4$, or even $P=2$?).

- Another is that there is generally very little spatial guidance from language as to where things in images are located (a guess, no concrete statistics here). There aren’t many examples of where a caption explicitly says “a person in the top right corner of the image running to the left”, or with explicit coordinates relative to the image. This also might be completely wrong, maybe Flickr/Pinterest have lots of these types of captions.

Fugue

Let’s change the game we’re playing now. I’m going to try and see how we can get these models to successfully solve this question in a reasonable* manner, where reasonable is a definition guided by vibes.

First, we’re going to ask it to solve the question allowing it to use code, a la ViperGPT/VisProg. At first, I get a cryptic response which is definitely correct, and it even mentions how it made a mistake previously when it wasn’t allowed to use code!

GPT-4V successfully solves the problem when allowed to use code

I had to prompt it to give me the code it used, which produced the following.

from PIL import Image

import numpy as np

# Load the image

img = Image.open("/mnt/data/random_4x4.png")

# Convert the image to RGB if it's not

if img.mode != 'RGB':

img = img.convert('RGB')

# Resize the image to 4x4 pixels

img_resized = img.resize((4,4))

# Convert the image to a numpy array

img_array = np.array(img_resized)

# Initialize a 4x4 text map

text_map = np.full((4, 4), ' ')

# Define a simple function to identify the color

def identify_color(rgb):

# Set a threshold for color detection

threshold = 120

if rgb[0] > threshold and rgb[1] < threshold and rgb[2] < threshold:

return 'R'

elif rgb[0] < threshold and rgb[1] > threshold and rgb[2] < threshold:

return 'G'

elif rgb[0] < threshold and rgb[1] < threshold and rgb[2] > threshold:

return 'B'

else:

return 'U' # Unknown color

# Loop over the array and assign the colors to the text map

for i in range(img_array.shape[0]):

for j in range(img_array.shape[1]):

text_map[i][j] = identify_color(img_array[i][j])

# The text_map contains the 4x4 grid with the identified colors

Hey! This code is cheating! It’s basically reducing the image naively to a 4x4 grid based on the information I told it, which doesn’t amount to any real understanding of the problem. In fact, it also gives some insight into when the model is wrong, it likely is trying to do something of the above but fails to.

Let’s not tell it that the input is of size 4x4 and re-prompt it again to see how it solves it now. Opening up a fresh session, I give it the following prompt.

Using code, recognize each image in the collage, then print out a grid text map with the convention R = red, G = green, B = blue.

Unexpectedly, it still gets it correct! Here’s the output code.

from PIL import Image

# Load the image

img = Image.open("/mnt/data/random_4x4.png")

# Convert the image to RGB

img_rgb = img.convert("RGB")

# Get the size of the image

width, height = img.size

# Initialize a grid map

grid_map = []

# Define a function to identify the color

def get_color_name(rgb):

if rgb == (255, 0, 0):

return 'R' # Red

elif rgb == (0, 255, 0):

return 'G' # Green

elif rgb == (0, 0, 255):

return 'B' # Blue

else:

return 'U' # Unknown

# Process the image by dividing it into a 4x4 grid

cell_width = width // 4

cell_height = height // 4

for y in range(0, height, cell_height):

row = []

for x in range(0, width, cell_width):

# Get the color of the center pixel of this cell

pixel_rgb = img_rgb.getpixel((x + cell_width // 2, y + cell_height // 2))

# Append the color abbreviation to the row

row.append(get_color_name(pixel_rgb))

# Append the row to the grid map

grid_map.append(row)

# Print the grid text map

for row in grid_map:

print(' '.join(row))

Now this is more reasonable. It’s getting the center pixel of each cell and using that as the color, which seems more robust. But wait, how did ChatGPT realize that it was a 4x4 grid with no prior context about it?

I realized then that it had to be from the name of the image! It was leaking information to the model. When I tried to get the model to tell me how it knew, it claims that it was done “without inspecting the actual image content, just its dimensions and the instructions provided.” Very clever from the model…

I once again prompted the model, but this time with an unassuming image title of just random.png.

from PIL import Image

import numpy as np

# Load the image

image_path = '/mnt/data/random.png'

image = Image.open(image_path)

# Convert the image to RGB if it is not

image = image.convert('RGB')

# Resize the image to a smaller size to analyze colors more easily

# Since it's a grid, we expect uniform colors in large enough areas, so resizing won't affect the outcome

image = image.resize((3, 3))

# Convert the image to a numpy array

image_array = np.array(image)

# Define a function to classify the color of a pixel

def classify_color(rgb):

# Set a threshold to differentiate between colors

threshold = 128

# Check if the color is closer to red, green, blue or black

if rgb[0] > threshold and rgb[1] < threshold and rgb[2] < threshold:

return 'R'

elif rgb[0] < threshold and rgb[1] > threshold and rgb[2] < threshold:

return 'G'

elif rgb[0] < threshold and rgb[1] < threshold and rgb[2] > threshold:

return 'B'

else:

return 'U' # U for undefined or mixed color

# Analyze each pixel in the 3x3 grid and classify its color

grid_text_map = [['' for _ in range(3)] for _ in range(3)]

for i in range(3):

for j in range(3):

grid_text_map[i][j] = classify_color(image_array[i, j])

grid_text_map

Aha! I just caught ChatGPT red-handed now. It’s trying to do the same trick it did at first, but assumes that the grid is a 3x3 since it doesn’t have any other cue to go off. Accordingly, the answer is off significantly; the dimensions don’t even match!

ChatGPT’s incorrect output when the image filename doesn’t leak information about grid size

I also tried the other obvious approach, which is to rename this 4x4 grid of squares to random_6x6.png and feed that in. Doing this actually completely short-circuited ChatGPT. It tried to generate code which failed/wouldn’t run three times in a row before stopping itself and failing to generate a response. Similarly feeding in a 10x10 grid without the proper hint resolution or even the wrong resolution leads it to give up, but telling it that it is a 10x10 grid lets it get the answer immediately as long as it can use code. Impressive at least!

Trying this with Google’s Gemini through Bard yields poor results. Even when prompting with knowledge that the result is a 4x4 grid and with the image name as a cue, it fails to generate anything sensical with code. Part of the reason is that Gemini actually renames all of its images to image.jpg, so there’s no leakage there. Interestingly, it also takes a different approach, instead finding the closest color between red, green, and blue by $\mathcal{L}_1$ distance for each pixel.

While code-based generations are very promising, the LVLM fails to even get to the code-based part correctly without picking up on shortcuts in our prompt. Are there better ways to prompt it to get this information on its own? In any case, this is a promising shortcoming that needs to be solved in these models before we can think about more difficult tasks.

Citation

If you found this post useful, you can cite it as:

@misc{zhu2023spatial,

author = {Zhu, Tyler},

title = {Remarks on Spatial Localization in VLMs},

year = {2023},

howpublished = {\url{https://blog.tylerzhu.com/2023/12/spatial-localization-vlms/}},

note = {Blog post}

}